Is Overtraining a Myth? (Real Life Examples)

This article will address overtraining and whether it’s a legitimate concern for bodybuilders or if its effects have been sensationalized.

There is a common belief in bodybuilding that if you train a muscle too long or too many times (without adequate rest days), you will enter a state of overtraining.

Overtraining is a catabolic state caused by excessive exercise. During this time, cortisol levels rise, resulting in a loss of muscle tissue and an increase in subcutaneous body fat.

Bodybuilders are particularly anxious about overtraining, thus ensuring they keep their workouts short (typically under 1 hour) and will only train 1 muscle group 1-2 times per week.

Some high-profile bodybuilders have voiced their opinions on overtraining. Rich Piana strongly put across his views in a 3-minute YouTube video, branding people as “lazy” and looking for “excuses.” This was due to comments from people accusing him of overtraining when he completed a 3-hour chest workout.

You can watch the video below:

CT Fletcher and Kali Muscle are other high-profile bodybuilders who agree with Rich Piana.

Contents

The Truth

Overtraining is largely exaggerated in bodybuilding. There is real-life evidence to suggest it’s almost impossible to overtrain a muscle directly.

However, it is possible to overstimulate your central nervous system, resulting in chronic fatigue in the muscles (known as overtraining).

Here are some real-life examples proving it’s extremely difficult to overtrain a muscle via weightlifting.

Proof: Overtraining is Exaggerated

If overtraining was common as a result of lifting weights for long periods of time, the following real-life examples could not exist:

Proof #1 – Gymnasts

Gymnasts have some of the most aesthetically pleasing physiques in the world, with many natural bodybuilders aspiring to replicate such muscularity.

Many Olympic gymnasts started out with ectomorph body structures, possessing insignificant amounts of muscle mass. However, after years of intense training, they can now be seen with exceptionally developed biceps, deltoids, and lats.

Ironically, gymnasts don’t intend to build muscle, as being heavier makes it increasingly difficult to perform their movements effectively. Instead, their objective is to be as strong as possible without adding bulk. Muscle is structurally dense, and thus anabolic steroid scandals are virtually non-existent in gymnastics due to AAS potentially worsening their performance.

A more common protocol for gymnasts is to take diuretic drugs (1), helping them to reduce water weight, thus giving them an unfair advantage.

Thus, we know that many gymnast’s muscular physiques are natural and the byproduct of the training they do.

Olympic gymnasts who compete on the rings and pommel horse have exceptionally well-developed biceps, triceps, lats, and deltoids, even compared to natural bodybuilders.

Thus, bodybuilders may ask the following questions:

- Why is gymnastics training significantly more effective than lifting weights?

- Should bodybuilders be performing calisthenics (gymnast movements) instead?

When observing amateur gymnasts who are yet to reach elite level, they too perform calisthenic exercises regularly; however, they have significantly less muscularity compared to older gymnasts at the Olympic level.

Olympic gymnasts‘ training is comprised of higher training volume, exercising for more hours throughout the week. This indicates that it is not exercise selection that is superior (compared to bodybuilding).

Instead, gymnast’s extensive training volume is likely the culprit for exceptional muscle hypertrophy.

Note: Bodybuilders also incorporate bodyweight movements (similar to gymnasts) into their training. This gives further evidence for the difference in growth being due to increased volume and TUT (time under tension).

Gymnast Volume vs Bodybuilder Volume

The average weightlifter trains arms once or twice per week. Thus giving a total of 1-2 hours of ‘volume’ for the biceps and triceps per week.

Gina Paulhus, who took part in the USA Olympic program, says gymnasts train for 30 hours a week (2). This equates to 6 hours a day x 5 times a week.

Gymnasts have six different events to train for: floor, pommel horse, still rings, vault, parallel bars, and horizontal bar.

Out of these six events, four stand out as being particularly demanding on the upper body: the pommel horse, rings, and the 2-bar events.

By subtracting 1 hour from the gymnast’s schedule to allow for a warm-up and warm-down, this gives them 5 hours to perform six different events.

Thus, practice for 50 minutes for each event. In total, the four demanding events that work the upper body add up to 200 minutes, or 3 hours and 20 minutes.

Multiply 3 hours by 20 minutes by 5 to get 16 hours of upper body per week.

In comparison, the average amount of volume a bodybuilder will train for is:

- 1 hour chest, 1 hour back, 1 hour arms, 30 minutes shoulders = 3 hours, 30 minutes

(Main muscle groups were trained during a 7-day duration.)

Conclusion: An Olympic gymnast’s muscles will be under tension for almost exactly 5 times longer in comparison to the average weightlifter.

This gives evidence to disprove the bodybuilding theory that training a muscle for more than 60 minutes in a workout multiple times per week is overtraining.

Real Life Proof #2 – Prisoners

Some people have observed friends and family enter prison and undergo exceptional physical transformations. There have been some theories as to why this is possible, but the general scientific consensus is unknown as to why prisoners experience such dramatic transformations.

Note: Some inmates do experience tremendous amounts of muscle growth due to them obtaining anabolic steroids inside. However, other prisoners also testify to getting muscular naturally. It’s common for family members and close friends of convicts to relay that the person didn’t take any drugs, with utmost confidence.

Prisoners are often on nutrient-deprived diets with low amounts of calories and protein. They are unlikely to have access to natural supplements and have limited access to the “weights” room, depending on the prison.

How Do Prisoners Build So Much Muscle?

The reason why some prisoners undergo dramatic body transformations (without the presence of steroids) is due to the principle of high-volume training and time under tension.

Although they don’t have ‘weights’ in their cells, prisoners still find ways to stimulate muscle growth in their rooms with exercises such as:

- Doing curls with a five-gallon jug filled with water

- Different variations of pushups, including standard, diamond, elevated, one-handed, and clap.

- Pull-ups or chin-ups may be possible (holding onto metal water pipes).

- Dips: using the edge of the bed

- Bodyweight squats/lunges

Bodybuilders can also perform these exercises in the gym; however, the difference is that prisoners have all day to workout.

For example, Charles Bronson says in his book, Solitairy Fitness, that he completed 2,000 pushups every day.

With the average weightlifter performing 1 hour of chest exercises a week, at least 30 minutes of that session are likely to consist of rest, leaving 30 minutes for actual exercise.

If 2 seconds per repetition are assumed (1 second for the concentric motion of the lift and 1 second for the eccentric), then 30 minutes divided by 2 seconds (1 rep) means that the average weightlifter will complete 900 repetitions of chest work per week.

Thus, if Charles Bronson and other inmates were performing 14,000 repetitions a week for chest, and the average weightlifter is doing 900 repetitions, prisoners like Bronson are doing up to 16x more reps.

There is a clear trend here: the more time a muscle is being worked, the bigger it grows.

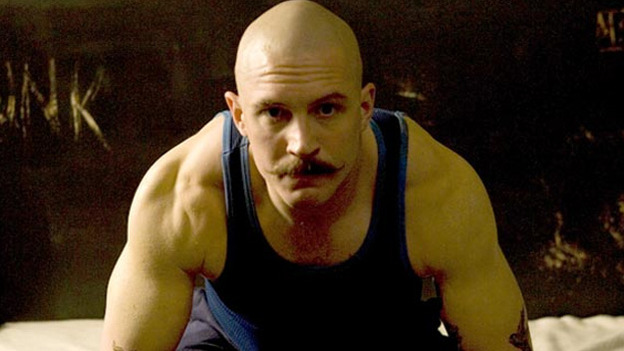

Real Life Proof #3 – Tom Platz

It is widely believed that Tom Platz had the greatest legs in bodybuilding history, resembling tree trunks.

Coincidentally, he is reported to have had leg workouts, which consisted of 3–4 hours of squats (3).

Platz also had incredible leg strength, reportedly squatting 227.5 kg for 23 reps. He admits that this strength was the result of training with lighter weights and performing higher repetitions (4).

His training philosophy of high volume and maximizing time under tension provides more evidence that such a methodology is capable of producing exceptional muscle growth and strength. Tom Platz’s legs would have been working for 2-3x longer, performing 23 reps, compared to the standard 6–10 bodybuilding rep range.

Other examples of high-volume training producing significant muscle growth are mechanic’s forearms, dancer’s calves, cyclist’s calves, and a gorilla’s arms.

In the last example, a gorilla’s arms look equally as big as their legs. Our theory as to why they have different proportions to humans in this regard is because they use all four limbs to walk throughout the day, thus creating a similar amount of time under tension for their legs and arms.

Such time spent under tension by walking on their arms (plus other physical exercise throughout the day) may be part of the reason why they have six times more power in their upper body compared to humans (5), and exceptional muscularity.

Some may argue that gorillas have vastly different DNA and genetics, but in reality, human genetics are 98% identical to a gorilla’s (6).

It IS Possible to Overtrain Your Central Nervous System

Overtraining is certainly real, despite being overexaggerated in bodybuilding.

When a bodybuilder lifts weights, it stimulates the central nervous system, producing higher levels of adrenaline and cortisol.

The higher stress hormones rise in the body, the more fatigued your muscles will become. This decreases your ability to recover and increases the risk of overtraining, whereby performance suffers.

Stephen from BuiltLean.com made an interesting analogy regarding your CNS and overtraining:

Overreaching vs Overtraining

Overreaching is essentially a mild form of overtraining, when an athlete becomes fatigued and performance decreases. Overreaching typically diminishes following a few days of rest (7).

Overtraining is more severe, caused by excessive exercise, in terms of intensity and duration. Full recovery from overtraining can take several weeks or months.

Here are some common symptoms of overtraining:

- Elevated resting heart rate (evidence of high adrenaline levels)

- Dehydrated. This is because the body is catabolic, often causing a dry mouth.

- Insomnia. Not being able to sleep is a common symptom of overtraining, as the nervous system is excessively stimulated, making it increasingly difficult to switch off.

- Depression. High levels of cortisol in the blood stream mean less testosterone and serotonin production. Testosterone, the male anabolic hormone, greatly impacts well-being. Serotonin is also a neutotransmitter present in the brain, responsible for feelings of happiness.

- Anxiety. Cortisol causes the body to enter “fight or flight” mode. Because overtraining causes an excessively aroused state, people may start to perceive harmless situations as threats, causing anxiety.

- Moody/Irritable. Higher cortisol levels can elicit negative mood changes. This is the same principle why people often become irritable when they haven’t eaten a meal for a long period of time.

- Becoming ill. This is a sign of a weakened immune system.

If overtraining is severe and the person doesn’t stop exercising, this can eventually result in the immune system becoming frail. Furthermore, a weakened immune system can increase the chances of cancer or other serious illnesses developing.

Thus, overtraining (when experienced in its true form) can be dangerous if rest isn’t taken.

Cortisol also increases blood pressure, increasing the chances of a heart attack or stroke. This has resulted in cortisol being nicknamed the ‘death hormone’.

Tip: Anyone experiencing symptoms of overreaching or overtraining may benefit from supplementing with 1000mg of vitamin C per day, which has been shown to slash cortisol levels significantly (8).

Are Bodybuilders at Risk of Overtraining?

The typical bodybuilder is at very low risk of overtraining, with it being one of the few sports in the world where the duration of exercise is minimal.

Those who are typically at risk of overtraining are professional athletes in sports that require several hours of training each day (at high intensities). Although professional athlete’s bodies have gradually adapted to handle such workloads over time, they can still become overtrained if a sudden increase in workload or intensity occurs.

Although lifting weights can stimulate the central nervous system, the average bodybuilder only trains for 1 hour each day. Thus, cortisol levels will not rise to excessive levels.

Soothing a stimulated CNS may allow athletes to train for longer periods without becoming overtrained.

If an athlete has a lot of stimulants in their diet, such as Coca-Cola, coffee, energy drinks, pre-workout supplements, and sugary foods and drinks, then they may be at a higher risk of overtraining.

This is due to the heart having to work harder at rest, and thus recovery is negatively impacted.

L-Tryptophan

Equally, there are certain foods and drinks that are effective in calming the CNS and reducing adrenaline levels, including:

- Eggs

- Chicken

- Turkey

- Mozzarella

- Cheese

- Milk.

The above foods and drinks are rich in l-tryptophan, an amino acid that soothes the nervous system, reducing adrenaline production.

L-tryptophan is the reason why many people enter a post-Christmas dinner slump, often resulting in a short sleep. This is due to turkey containing l-tryptophan. Research has shown that consuming carbohydrates with l-tryptophan increases their absorption. Potatoes aid in this process and are also included in Christmas dinners.

The quantity of food a person eats can also affect the CNS. Being in a calorie deficit has been shown to increase cortisol levels considerably (9). Eating in a calorie surplus produces a sedative effect on the nervous system, reducing the chances of overtraining.

Lack of sleep can also increase the chances of overtraining. The recommended sleep duration is 7-9 hours (10). If sleep is compromised, then you can experience a cortisol increase of as much as 45% (11).

Summary

In this article, we concluded that overtraining is somewhat common in elite athletes (12), but very rare in bodybuilding. This is due to the minimal time spent lifting weights by modern bodybuilders.

Overreaching in bodybuilding remains possible (13), should stress hormones such as cortisol become excessively elevated through a severe lack of food or sleep.

However, assuming a bodybuilder achieves a normal duration of sleep, eats adequate amounts of food, and is under normal levels of stress, overtraining is extremely unlikely (14).

From our real-life observations, it’s seemingly impossible or extremely difficult to directly overtrain a muscle by lifting weights.

This is why gymnasts, prisoners, and others are able to train the same muscle groups for hours each day with extraordinary results.

Put this principle to the test: perform 400 push-ups a day for 30 days and see how your triceps and chest transform.

References

(1) https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2962812/

(2) https://www.bodybuilding.com/fun/how_gymnasts_train.htm

(3) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fRKLLqZXfVs

(4) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=61XaQSWhFKk

(5) https://seaworld.org/animals/all-about/gorilla/characteristics/

(6) https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/tiny-genetic-differences-between-humans-and-other-primates-pervade-the-genome/

(7) https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9068095

(8) https://www.psychologytoday.com/intl/articles/200304/vitamin-c-stress-buster

(9) https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2895000/

(10) https://www.sleepfoundation.org/press-release/national-sleep-foundation-recommends-new-sleep-times#targetText=Teenagers%20(14%2D17)%3A%20Sleep,8%20hours%20(new%20age%20category)

(11) https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9415946

(12) https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3435910/

(13) https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32602418/

(14) https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6859241/

Inside Bodybuilding is a team of medical professionals and physicians with specialized knowledge and experience regarding bodybuilding and PEDs.