The History of the Plank Exercise

The chances are that every single one of us has spent a seemingly endless amount of time stuck in the ‘plank’ position shown above. When I first began weight training for rugby as a starry-eyed teen, we did every kind of plank variation imaginable.

We did it for time; we moved in circles, added weights, and even at times placed each other on our backs to increase resistance and improve our core strength.

Was it all a waste of time? Probably, if truth be told.

Though one can feel the effects of the plank on their abdominals almost instantly, any pain I suffered from having a weak ‘core’, that oh so mercurial term, was eventually solved through copious amounts of squats, deadlifts, reverse hyperextension, and back extensions combined with strict cable crunches and hanging leg raises. If these exercises don’t challenge your core, I’d suggest re-evaluating your form.

In any case, it’s undeniable that the plank exercise has become a mainstay in the fitness community over the past two decades. Though it’s fading out in my own gym, at least somewhat, it’s still used by numerous personal trainers and classes the world over. This leads us to the point of today’s post. Who invented the plank exercise, and how did it become so damn popular? Furthermore, is it actually beneficial? I’ll put my own prejudices aside as best I can for the last point.

Who invented the plank?

As someone currently doing a PhD on physical culture in the early twentieth century, I like to think that I can at least do some research. As is so often the case, trying to uncover the history of certain exercises smashes my fragile ego into so many pieces. This is a very roundabout way of saying that I simply cannot pinpoint when the plank exercise was invented.

What I can do, however, is tell you about some precursors who helped popularize the movement, making my useless PhD slightly less useless, I think.

After spending several days on this point, a common theme has emerged. Specifically, people have cited Joseph Pilates, the man behind the Pilates school of training, as the inventor of the plank. Unlike modern iterations, which valorize the amount of time held in this position, Pilates supposedly used the exercise for reps and strength as opposed to endurance. When people cite Pilates as the precursor, they’re generally referring to the Leg Pull Front exercise shown below, which, again, cards on the table, I have no real experience with.

So, the Pilates system of training emerged in the 1920s, the story of which we’ll cover in a later post, which definitely seems to lend credence to claims that Joseph Pilates invented a plank-esque exercise.

Another thought that struck me was the invention of the burpee. Try to remember the last time you did a round of burpees. I usually block it out, but try. One segment of the move includes a plank-style hold in the push-up position. As we know from previous blog posts, the Burpee was promoted in the late 1930s and early 1940s by Mr. Royal H. Burpee, possibly the greatest name of all time. Even if Pilates bested Burpee, a sentence I never thought I’d write, by a decade or so, it’s possible to say that combined, both men helped to promote early precursors of the plank.

What happened in the following decades has proven to be the greatest mystery to me. Both pilates and the burpee continued to be used, but we were a long way from the ‘Core’ craze, which seemed to hold the plank exercise at its forefront. What happened?

Enter Stuart McGill.

If you’ve been around the dark recesses of the internet occupied by the lifting community, chances are that you’ve come across Dr. Stuart McGill at some point. Based at the University of Waterloo in Canada, McGill’s life work seems to be the eradication of lower and general back pain as well as the promotion of spine-friendly abdominal work. We have seen McGill’s work over the past two and a half decades have a substantial impact on the lifting community. Thanks in part to him, my beloved Russian twists have largely become a thing of the past, and even the traditional sit-up has come under fire.

When McGill speaks, people listen, and this is precisely why our story now comes to him. As early as 1999, McGill was co-publishing work on bridges and side bridges in relation to stabilizing the lower back. By 2003, McGill himself was producing work for personal trainers directly related to the plank and side plank exercises (see here).

From the McGill 2003 paper cited above.

From the McGill 2003 paper cited above.

Was McGill a one-man force in promoting the plank? No, of course not, but he was a hugely influential voice. People listened.

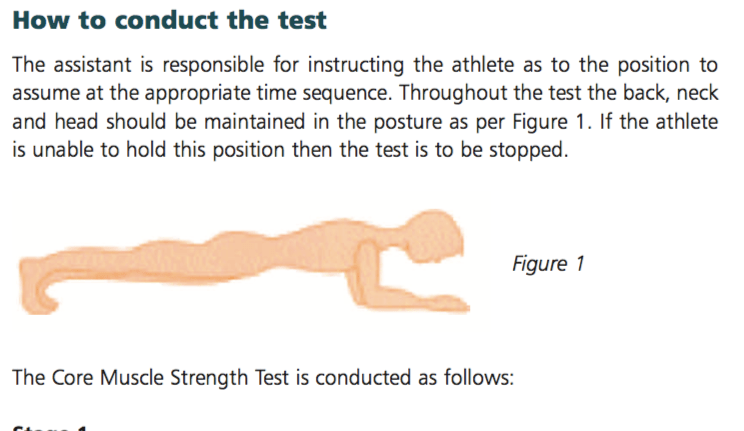

In 2005, Brian MacKenzie introduced 101 Evaluation Tests for athletes and the lay public, covering a range of different tests, including the plank exercise.

Brian MacKenzie, 101 Evaluation Tests (London, 2005), p. 111

Brian MacKenzie, 101 Evaluation Tests (London, 2005), p. 111

For teenage Conor, the MacKenzie tests were responsible for a barrage of sprinting, jumping, and weightlifting on a regular basis.

The plank, then, was growing in popularity. Both personal trainers and the lay public were beginning to use it as we reached the height of the ‘core training’ craze, which I’ll probably cover very cynically in future posts. Personal training certifications, such as Ace Fitness (1), began to wax lyrical about it, and the sit-up was being replaced by the plank. This didn’t go unnoticed.

In 2009, the International Association of Fire Fighters dropped the sit-up requirement in favor of a plank test at the behest of McGill and others in the field. That same year, word came from the US Army that planks may be included within their own entrance criteria for the sit-up. At the time of writing, this has yet to happen, it seems, although please correct me if I’m wrong.

That very identifiable institutions were dropping or considering dropping the sit-up in favor of the plank was important for the very simple reason that it was reported widely. The plank thus grew in the public imagination.

Are planks worth doing?

According to the International Sports Science Association, planks are one of the most effective abdominal exercises one can do (2). They protect the spine, engage the abdominals, and are easy to teach. Furthermore, the crossover from the exercise to other fields is seen as greater.

For those of you interested in different variations of the plank, I’d like to direct you here.

Anecdotally, I have found that, of course, the plank exercise has its place, especially for beginners or those overcoming injuries (3). From my personal experience, however, I’m a little more skeptical. I spent easily five years devoting time to every plank variation you can imagine, and it was not until I readdressed my form on big lifts like squats and deadlifts that I began to truly stabilize my lower back (and by readdressing my form, I am referring to bracing correctly).

I combined squats and deadlifts with other larger movements for the posterior chain, along with strict abdominal work. This has improved my strength far more than planks ever did. At the end of the day, or workout, I suppose, it comes down to what your goals are and how useful the exercise is. I would be interested in learning how many of our readers incorporate the plank on a regular basis and how beneficial they find it.

Dr. Conor Heffernan was an assistant professor of sport studies and physical culture at the University of Texas, Austin. Dr. Heffernan now resides in Belfast, providing sociology of sport lectures at Ulster University, which specializes in European and American health. Dr. Heffernan’s work examines the transitioning nature of diets in the twentieth century.

References

(1) https://www.acefitness.org/education-and-resources/professional/prosource/february-2014/3680/reality-check-are-planks-really-the-best-core-exercise

(2) https://www.issaonline.edu/blog/index.cfm/2016/are-sit-ups-bad-for-you-the-us-military-seems-to-think-so

(3) https://www.btetechnologies.com/therapyspark/planks-the-do-it-all-exercise-for-rehab-and-fitness/