The History of Calorie Counting

Ah, yes, the much-maligned calorie. Whether you’ve ever tried to lose weight, put on mass, or even just feel okay about eating junk food, chances are you’ve come across those pesky calorie numbers on food labels. You may be surprised to learn that despite the ubiquity of calorie counting in today’s society, this unit of measurement is a relatively recent phenomenon, and the idea of counting calories for health purposes is even newer.

In today’s post, we’re going to look at who invented the calorie, how calorie counting became popular, and finally, how calorie counting became the mainstay of bodybuilding diets.

Contents

Who Invented the Calorie?

Although some state that Favre and Silbermann first coined the term calorie in 1852, recent studies into the calorie’s origins tell a different story. Between 1819 and 1824, it is said that French physicist and chemist Nicholas Clément introduced the term calories in lectures on heat engines to his Parisian students. His new word, ‘Calorie’, proved popular, and by 1845, the word appeared in Bescherelle’s Dictionnaire National.

By the 1860s, the term had entered the English language following translations of Adolphe Ganot’s French physics text, which defined a calorie as the heat needed to raise the temperature of 1 kg of water from 0 to 1°C. By the 1880s, the term was first introduced to the American public by Edward Atkinson in 1886. Professor Wilbur O. Atwater came next when he published on the calorie in 1887 in Century Magazine and again in the 1890s in Farmer’s Bulletin.

We find that Atwater was, in many ways, the driving force behind the calorie’s popularity. In the 1890s, Atwater and his team at Wesleyan undertook an exhaustive study into the caloric content of over 500 foods with the intent of producing a scientific and healthy way of maintaining one’s weight. By the early 1900s, Atwater was one of the leading authorities on dietary intake, and his advice was simple. Cut out the excess and ensure a balance between foods.

Unless care is exercised in selecting food, a diet may result in one that is one-sided or badly balanced, that is, one in which either protein or fuel ingredients (carbohydrate and fat) are provided in excess. The evils of overeating may not be felt at once, but sooner or later they are sure to appear, perhaps in an excessive amount of fatty tissue, perhaps in general debility, perhaps in actual disease.

Atwater, 1902.

Who popularized calorie counting?

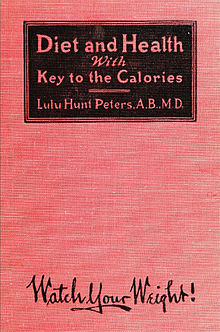

While Atkinson and Atwater were advocating for dietary restrictions based on calorie contents, it took some time before the idea of calorie counting became a mainstay in American diets. In 1918, American physician, author, and philanthropist Lulu Hunt Peters changed the face of dieting for the next century. Seeking to write a diet book targeted at American women, Peters latched onto the idea that calorie counting was an effective means of enacting healthy weight loss. With this idea in mind, Peters got to work.

For years, Peters had written a number of newspaper columns for the Central Press Association entitled ‘Diet and Health’, which dealt with issues of health and weight. Proving popular with her audience, namely middle-aged American women, Peters was encouraged to collect her writings into one neat volume, something she did in 1918.

Under the title ‘Diet & Health: With Key to the Calories’, Peters published her first and only book on calorie counting. Fortunately for Peters, one book was all she needed. Diet & Health became one of the first modern dieting books to become a bestseller, and it remained in the top ten non-fiction bestselling books from 1922 to 1926.

So what made Peters’ book so attractive? Well, a number of things…

- First, it took the rather complicated idea of calories and simplified it for a mass audience. Peters told readers that henceforth, they would view all their food in terms of calories. A slice of bread was no longer a slice; it was 100 calories of bread.

- Second, Peters had a keen understanding of the psychological roadblocks one encounters when trying to lose weight. For example, she discussed the dangers of passively aggressive partners, unsupportive peer groups, and cravings as topics one must be alerted to.

- Finally, Peters’ advice was effective. Eat roughly 1,200 calories a day from whatever food group you desire (if it fits your macros, anyone?) and lose weight. The only exception to this was candy, which Peters advised against, believing it too easy to binge on. Regarding the efficacy of her system, Peters informed readers she herself had weighed upwards of 200 lbs. before dropping 50–70 lbs. eating this way.

Interestingly, for athletes and bodybuilders, Peters’ advice on gaining and losing weight will seem very familiar. To calculate your basic caloric needs, she recommended multiplying your bodyweight by 15-20 to find the magic number. If you need to lose weight, eat 200–1000 calories less, and if you need to gain weight, eat 200–1000 calories more. Fun facts aside, Peters was undoubtedly hugely influential in popularizing calorie counting for the general public. A trend that began in the late 1910s and continues to this very day.

When, how, and why did bodybuilders take up calorie counting?

Given that calorie counting became a recognized means of dieting in the 1910s, it’s remarkable to think that bodybuilders took to it so late.

When we read the dietary advice of men like Eugen Sandow or George Hackenschmidt, we find no mention of calories. What we do find is a strong emphasis on eating natural, unprocessed foods. Fast forward even to the likes of Reg Park and John Grimek, and the advice stays the same. To build muscle, you were encouraged to eat more. To lean out, you had to eat less and perform more volume in your workouts.

Heck, even Arnold, Zane, and co. appeared to function without the need to count calories. Ric Drasin has routinely discussed the ketogenic diets favored by ‘Golden Age’ bodybuilders, suggesting that the elite bodybuilders of the 1970s took a drastically different approach to food than today’s lot.

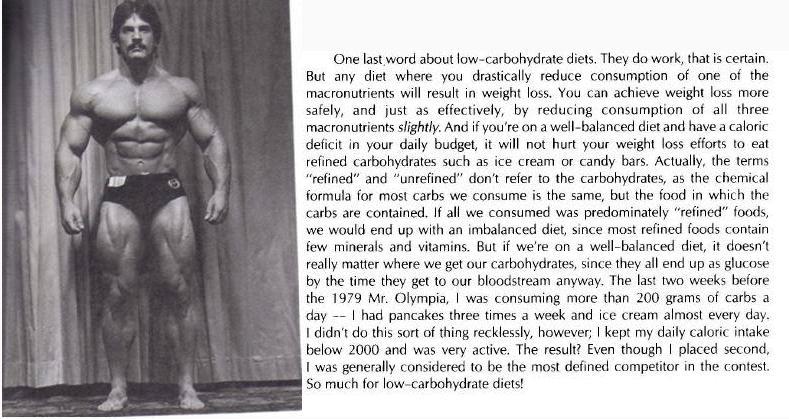

Despite this, we have some evidence of calorie counting creeping in during this time. As part of his participation in Arthur Jones’ infamous ‘Colorado Experiment’, Casey Viator consumed 800 calories a day to bring himself down to an emaciated 168 lbs. During the 28-day experiment, he upped his caloric intake to roughly 5,000 calories a day. Something that may explain his alleged 45-pound weight gain in 28 days (1). By the 1979 Olympia, Mike Mentzer, another Jones’ disciple, was using calorie counting to manipulate his physique. As an interesting side note, the following Mentzer quote is often taken to justify that anything goes if it fits your macros approach’.

While bodybuilders were tentatively experimenting with calorie counting during the 1970s, we saw the practice truly come to the fore in the 1980s when Rich Gaspari and Lee Labrada utilized calorie counting to produce some truly stellar physiques. In 1988, Rich Gaspari revealed to the makers of Battle for the Gold, a bodybuilding documentary now available on YouTube (2), that he calculated his caloric intake to the tee, weighing everything and generally eating an incredibly strict diet.

Gaspari with his nutritional ‘bible’

By then, Gaspari had clearly demonstrated the efficacy of his approach. In many ways, Gaspari’s calorie counting changed the face of bodybuilding. You see, at the 1986 IFBB Pro World contests, Gaspari revealed his striated glutes to the judges and audience, setting a new standard for leanness that has continued to this very day.

Gaspari’s glutes in all their glory

Since then, bodybuilders, both natural and enhanced, have taken to calorie counting to achieve a similar level of leanness. While the practice of counting calories is fraught with problems, we find it to be the most effective way of reducing one’s body fat to the levels needed for competitive bodybuilding (3).

References

(1) https://www.t-nation.com/workouts/the-colorado-experiment-fact-or-fiction/

(2) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xF8jsrdgGD0

(3) https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18025815/

Dr. Conor Heffernan was an assistant professor of sport studies and physical culture at the University of Texas, Austin. Dr. Heffernan now resides in Belfast, providing sociology of sport lectures at Ulster University, which specializes in European and American health. Dr. Heffernan’s work examines the transitioning nature of diets in the twentieth century.